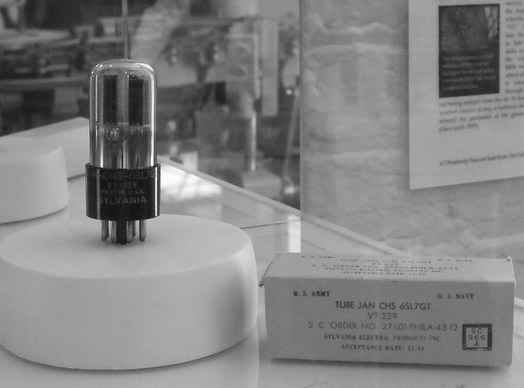

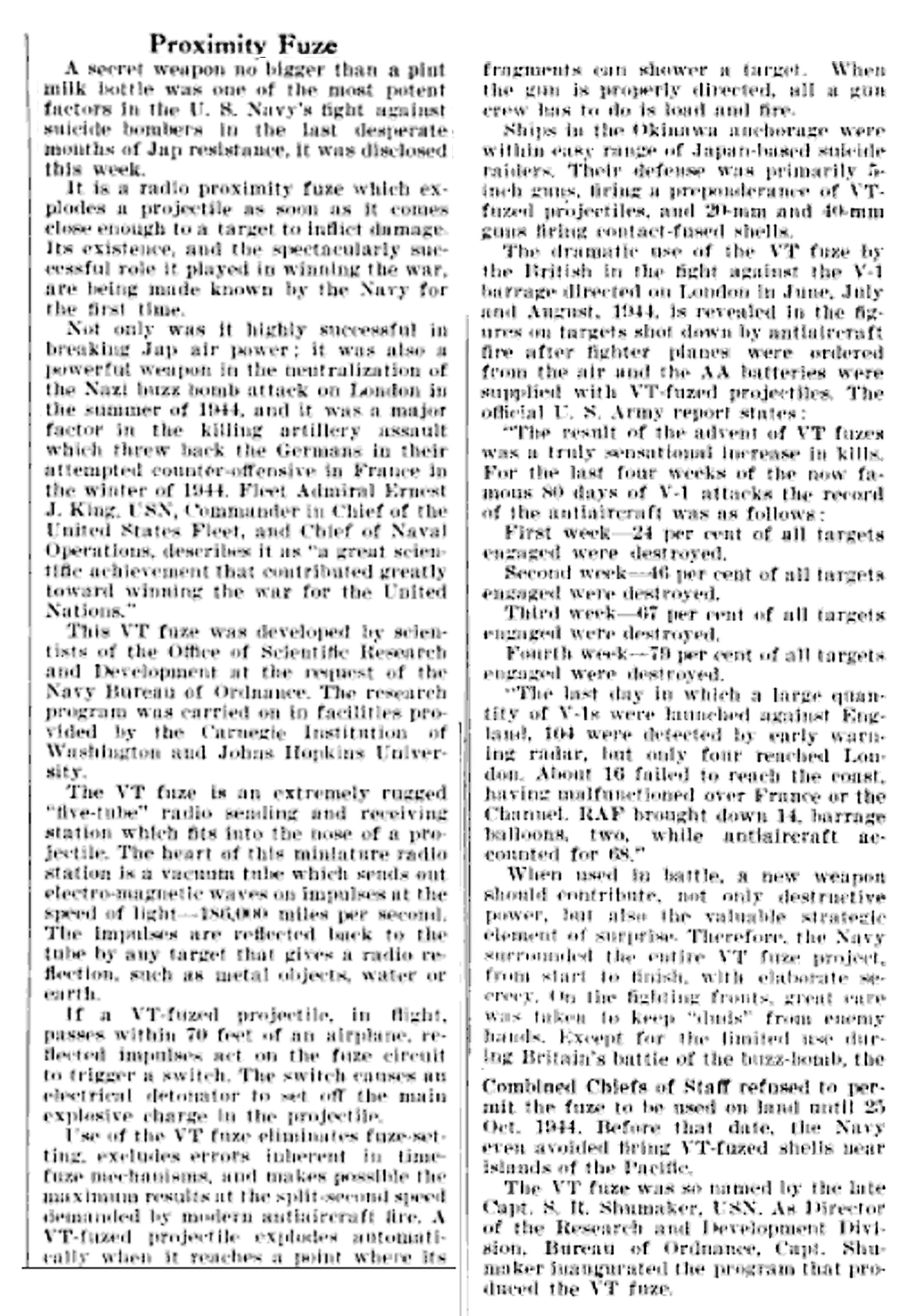

The former Ipswich Mills, now owned by EBSCO, was the site of one of the most closely guarded secrets of the Second World War. The VT proximity fuze (variable time fuze) resembled tubes found in radios and made it possible to detonate antiaircraft shells above or in the proximity of their targets, rather than on impact. This new trigger mechanism increased the lethality of bombs dropped by a factor of 10 compared to exploding on ground contact.

Fearing that the secret of the invention might fall into enemy hands, the very existence of the proximity fuze was top secret, second only to the Manhattan Project which developed the atomic bomb. For most of the war, the Pentagon even refused to allow use of the proximity fuze by the other Allied nations.

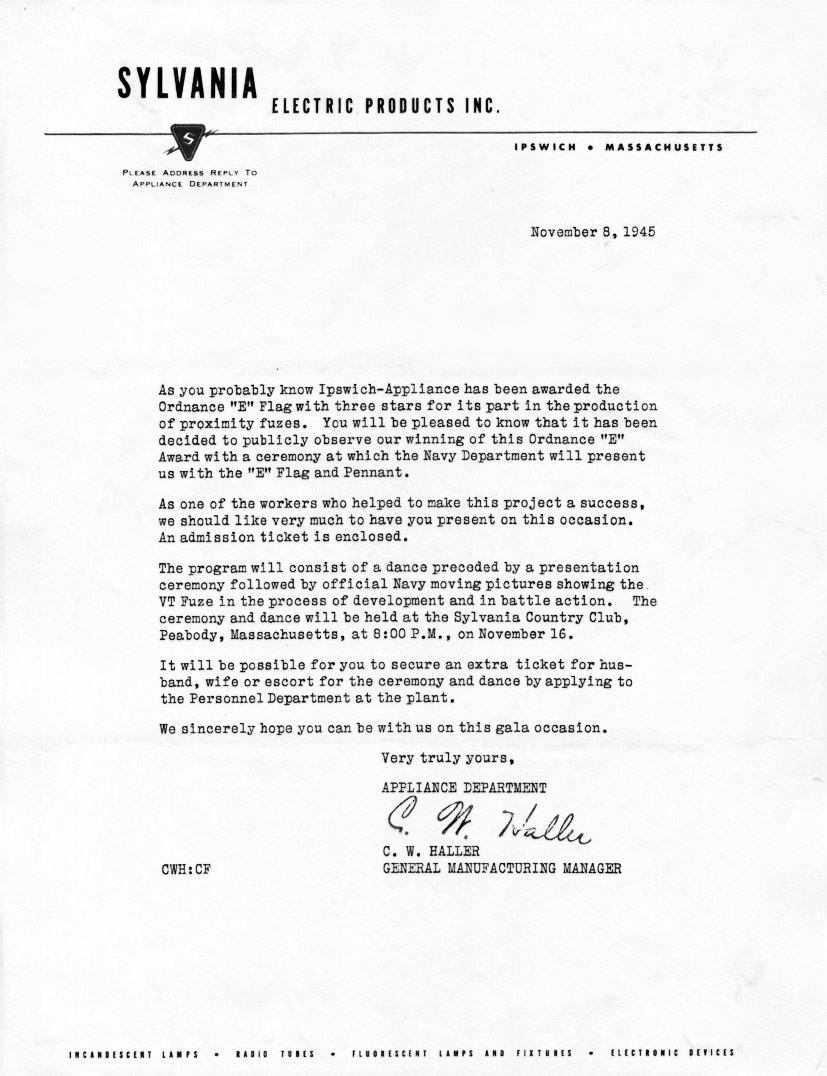

Mass production of the miniature tubes was granted to Sylvania Electric Product, the only company capable of the required quality and quantity. Sylvania plants in Pennsylvania, Ipswich, and other areas were retooled to manufacture the devices. The job of producing the fuzes was primarily given to women, who assembled the delicate parts by hand by the hundreds, a tedious job that strained the eyes. The women were not told what they were working on, and the work was done under such secrecy that they were searched when they entered and left, and were not allowed to enter the plant with a purse. Even the Ipswich Police or Fire Department were permitted to enter the building. By 1945, hundreds of women across America had assembled over eight million proximity fuzes for the war effort.

In 1943, 36,000 of the fuzes were fired and were responsible for the destruction of 91 of 130 attacking Japanese planes, protecting ships and servicemen from Kamikaze pilots. When German forces began systematically destroying London in 1944 with V-1 rockets, the technology was shared with Britain. By the final day of Germany’s 80-day attack, only 4 of 104 bombs succeeded in reaching their targets.

By 1944, proximity fuzes were being made by Crosley, RCA, Eastman Kodak, McQuay-Norris, and Sylvania in Ipswich, which produced 5,683,032 fuzes, the most of any location.

In December 1944, Germany launched a ground attack, known as the Battle of the Bulge. Allied forces responded by bombarding German ground forces with shells equipped with proximity fuzes, spraying shrapnel as they exploded over the heads of the German troops. Gen. George Patton credited the proximity fuze with victory in Europe.

Some of the Ipswich people who worked on the proximity fuzes

- Roslyn (Comeau) Amerio

- Gerry Benjamin

- Vincent Byron Bennett

- Mary Blunda

- Virginia Bower

- Winifred Brierly

- Grace Brooks

- Ethel Markos Campbell

- Helen Christopher

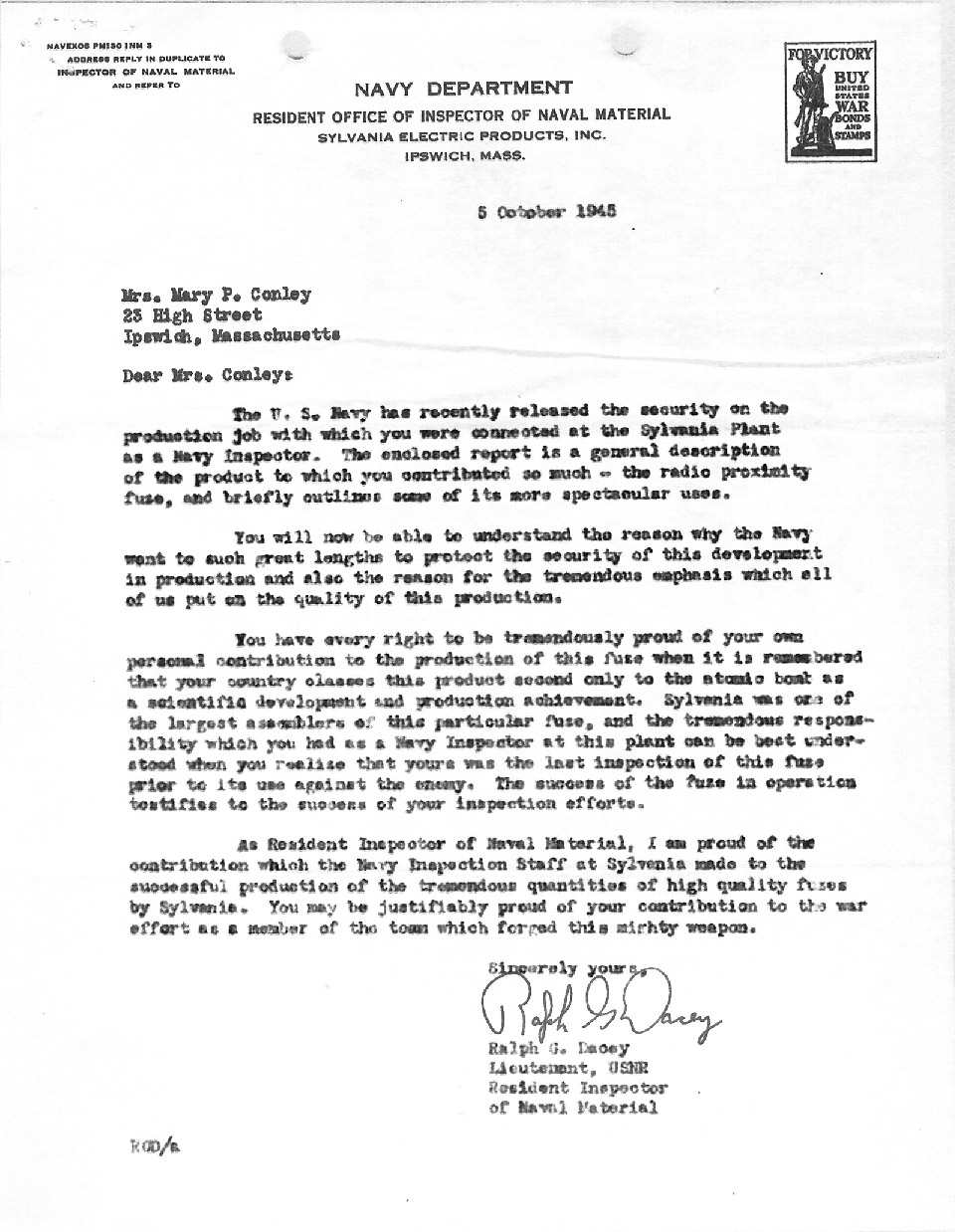

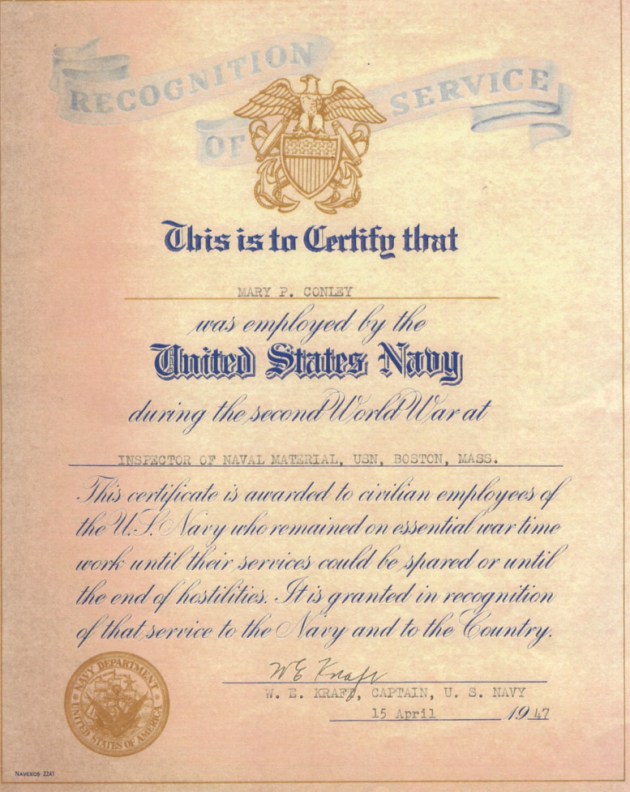

- Mary P. Conley

- Margaret Courage

- Gwendolyn Davidson

- Elizabeth Gangi

- Marie-Anne (Martel) Hall

- Emelie Hannah

- Florence Hill

- Phyllis B. (Garrette) Hills

- Doris (Martel) Hinckley

- Louise Huard

- Marie Lorraine Kelley (Cook)

- Kay Kellie

- Bertha Knice

- Jennie Catherine Kozeneski

- Evelyn Strok Lachowicz

- Bessie Lampropolous

- Sylvia Little

- Grace Lombard

- Myrtle Lyman

- Lorette Marchand

- Virginia Marcorelle

- Florence Marshall

- Audrey Martineau

- Ruth McCormack

- Theodore Melanson

- Phyllis Perkins

- Kitty Crockett Robertson

- Victoria K. Scibisz

- Katherine Shurcliff

- Alyce Somers

- Jean Sullivan

- Victoria Terentowies

- Helen E. Thurber

- Wilbur E. Trask

- Myrie Wonson

Please use the comment box to add more names to this list.

1944 Ipswich Town Report: Electrical Department

“Nearly 8 million kilowatt hours of electricity were produced at the town power plant during the year 1944, an increase of 21 percent over the previous year. This was done with the same machinery and labor as in 1942 when the output of KW hours was 5 1/2 million, representing an increase in the three-year period of 32 percent. The Town was fortunate in having installed in 1941 a new generating unit without which we would not have been able to supply the demands for electric power called for by the Sylvania Plant and Robinson’s Shipyard.”

In May 1945, the war in Europe ended with the defeat of Hitler’s armed forces. When news reached the town of the surrender of Japan in August, an impromptu parade was held downtown to celebrate the victory. Thirty Ipswich men and one woman gave their lives in service to their country.

Sources:

- wikiwand.com/en/Proximity_fuze

- Wikipedia: Proximity Fuze

- mecc.org/radio_proximity_fuzes.htm

- Proximity Fuze Manufacturers of World War Two

Fascinating details about local involvement in WWII preparation. These women look happy in their work. But, oh, how deadly these fuses were….

Roslyn (Comeau) Amerio

Mary P. Conley

My mother had a job singing the Sylvania radio theme song during that time with I think a quartet. Lorette Marchand of Ipswich. I still know the song from her singing it for us.

Annie Scott Lynch who lived at 16 Elm Street. Annie’s war work and the actual house are featured in the National Museum of American History exhibition Within These Walls…

My Mother Doris (Martel) Hinckley

Please record the Sylvania Blue Dot theme song.

Virginia Bower, a summer resident of Little Neck, worked one summer at the Sylvania plant building proximity fuzes. She always said it was a secret weapon.

My grandfather, Henry Trask Cowles, worked at the Sylvania plant in Ipswich after he retired as a professor of agriculture in Mayaguez, Puerto Rico. My mother says he fixed fuzes that didn’t look right upon inspection.

Very interesting article; it’s true no one knew exactly what they were making while they were working there.

They learned more about the fuzes after the war, but my grandfather was always a little bit vague about them.

Sincerely, Susan Cowles

Thank you Susan. I can’t help but ask, are you related to John P. Cowles and Eunice Caldwell of the Ipswich Female Academy?

My mother, Ruth Horn, worked on this project. She was diagnosed with malignant mesothelioma 20 years ago. When the doctor asked where she had worked she replied Sylvania. The doctor asked her what she did. She said she didn’t know, it was a secret. She thought she was soldering the tips of lightbulbs. After she had died I did some research into her employment at Sylvania and discovered that she was actually making proximity fuses. I also discovered that the material she had used to solder was beryllium. Beryllium does cause lung cancer and it can have a 60 year latency period. I believe that this is what killed my mother. I’m not sure if any of the other women who worked at Sylvania at the time contracted Malignant Mesothelioma but if they did they should be honored. I registered my mother in the WWll Women’s memorial in DC. I believe that all the women listed above should be honored and listed in the WWll Women’s Memorial. God bless them all.

Mary Blunda was a supervisor who also worked on this project

Looking through my mother’s papers, I find a card that originally held a pin. The card is from the Bureau of Ordinance, U. S. Navy which extends congratulations, and an “E” insignia to the men and women who participated in the production of the proximity fuze. It seems this card originally held an Army-Navy E insignia. Anyone else who’s mother worked on the proximity fuze find information about the company getting the Army-Navy E emblem, and our mothers receiving “E” insignias?

My Mother, Elizabeth Gangi, from the neighboring town of Topsfield supervised these unsung heroes at Sylvania. So proud of her and would love to honor her memory by having her listed.

Anna vantine worked at john Hopkins applied laboratory in Maryland for33 years

Also worked on the TV fuse she is in the company’s newspaper. Richard saunders I lived with her the last 7 years of her life. 407 860 2871 she was 85 when she passed.

I always wondered how they worked. and the spray over water when they burst . The water always looks like it was being sprayed with something, it was, sharapnel!

And a tremendous shock wave.

absolutely a shock wave. It it alway bugged me how they worked, and then when you see one explode near a plane, over water, you see weird sleet like stuff going down, as the plane gets mangled, exploded. Almost like pebbles, except they were substantial chunks of steel shards!

Pat Vlahos, my mother, also worked there for years. Unfortunately I don’t have the exact dates.

Yes!

Annie Scott Lynch is featured at the Smithsonian for living at the Elm Street House and working on the Proximity Fuze

Our Mother worked as a currier traveling from New Hampshire to Ipswich with engineers plans for

Proximity fuze, she told us she travelled with 2 armed guards when

Traveling with plans between sylvania

Plants during the war. Her name was

Winifred Brierly from Dover New Hampshire.

My grandfather, Vincent Byron Bennett, of Argilla Road, also worked at the factory during the war, he balanced the rotars. Many of the names on the list are familiar to me, from memories he shared of neighbors and friends.